TOMBSTONE ARIZONA'S HISTORY & INFORMATION JOURNAL

TOMBSTONE ARIZONA'S HISTORY & INFORMATION JOURNAL

Chinese Residents in Tombstone Arizona

by Sam Shueh and Eric Chen

From the December 2006 issue of Tombstone Times

Chinese Residents in Tombstone Arizona

by Sam Shueh and Eric Chen

From the December 2006 issue of Tombstone Times

Tombstone, Arizona, is situated southeast of Tucson and has a current population of over 1,500. It has a rich history and is best known for having been a lawless town during the 19th century. The town was made up largely of single men, most of whom were employed by mining companies. The miners worked 60-hour weeks and played hard on their days off. Tombstone was made famous by the gunfight in which Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday shot Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury, and Frank McLaury behind the O.K. Corral. The town became the setting for no fewer than 30 western movies.

The history of Tombstone's Chinese residents, although mostly forgotten, is fascinating as well. Most books written during the period depicted Chinese Americans as drug traffickers and people who loved gambling. One Arizona tourism website cites a historic source that claimed, "The Chinese are highly immoral; they sell children, exercising a system of female slavery." In a 19th-century U.S. census, Chinese females in the west always declared their profession as "prostitutes." On the whole, however, the Chinese were industrious and law abiding. They retained their own heritage and kept very much to themselves.

Around 1870, hundreds of Chinese were employed in the construction of the Southern Pacific railroad through Arizona. Many of these workers were from the Pearl River delta area of Guangdong province. Although the area was an overpopulated poor county at the time, Zhongshan, just north of Macao, is now a modern industrialized city of over a million residents, $4.4 billion in exports annually, and enjoyed a capital income of US $32,000 during year of 2000.

The early Chinese migrant workers came to America through an employment contractor for whom they were to work for a stated term - typically a few years. The business of hiring and managing the employees' affairs was controlled by Chinese Tai Pan and businessmen. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, more commonly known as the Chinese Six Companies (because it represented different regions of Guangdong province), dealt with U.S. immigration matters at the city and state government levels. The Six Companies, which is still in existence, was the most powerful organization acting on behalf of the Chinese outside of China.

Earlier U.S. sources misunderstood the function of Tongs (offices) such as the Six Companies and thought they were involved in gang warfare and selling slaves, as portrayed in Jackie Chan's action-filled movie Shanghai Noon. Tongs actually offered the most advanced employment contracts of the time. The associations paid the workers'passages, found employers, and took care of the employees when they became ill. They were also responsible for sending money home, and they acted as bankers and mail service providers. These services were essential, as the immigrants did not trust the U.S. banking system or Wells Fargo, given the frequent shootouts and robberies. The contractor deducted money for dormitory, food, boat fare, medicine, and also a percentage for its services. The function of Tong acted as a middle man go between for workers and employers. It attempts to guarantee a certain amount of laborers, while proving a safety net for employees.

The workers accepted the premise that they come to America to work hard for a few years so they could pay off their debt to the company. If they earned enough money in Gum Shan (i.e., Golden Mountain), they could return to China and raise a family. In the unfortunate event they died on foreign soil, their remains and soul would be packed and sent home. They were first buried in the Chinese section of a U.S. cemetery. After a year or so, caretakers dug the bodies up, cleaned and soaked the bones in brandy wine (which acted as a preservative), wrapped them in fine silk cloth, and sealed them in an urn. The remains were never wrapped in paper, as was claimed by some early American writers.

When the railroad construction was completed, all the Chinese laborers were let go immediately. The competition of less intensive jobs filled by the whites resulted in the Chinese exclusion Act of 1882. Born survivors, the Chinese managed to settle in nearby towns, finding work in the mines or being redeployed into the service industry. They accepted whatever positions they could get. They worked as woodcutters, miners, cooks, or servants; worked at charcoal manufacturers; or grew vegetables. Most had been farmers in China, and they quickly adapted to the local farming environment. Opportunities arose in work that other men found to be time consuming and undignified, such as doing laundry by hand. Several hundred Chinese settled in Tombstone during the Arizona silver boom of the 1880s.

The Chinese were first regarded with open suspicion by the people of Tombstone, mainly because of their unusual appearance and cultural traits. The men all wore their hair in a queue or pigtail (a subjugation gesture required by the Manchu government, which ruled China from 1644 to 1911). Of the few women who came, some had bound feet. To the puzzlement of other locals, the Chinese drank boiled water infused with "tree leaves" (tea) as a precaution against illness. They ate with wooden sticks while squatting without a chair to sit upon.

White saloon owners, storekeepers, and gamblers bitterly rejected acceptance of the Chinese. The Chinese were included in the Western U.S. census, but in Arizona they were excluded from the state census and not included in the marriage licenses (although they have criminal records). The Whites depended, however, on the work of the Chinese coolies (ku li, meaning hard laborer), who had good work habits and who were willing to do anything for less pay. Despite the harsh wide social gulf that separated them from other people, the Chinese demonstrated a compassion and a recognition of their own value.

Like most cities, Tombstone had its Chinatown. Whites called it "Hoptown." It hopped from Third Street to First Street and from Fremont Street to Toughnut Street. To avoid trouble with residents in other parts of the town, the Chinese hopped in and out of connecting private tunnels. In a town of more than 5000, perhaps 300 to 500 were Chinese who lived in their own quarters.

Pak Gaw, White Dove (i.e., Keno), Mah Jong, and western poker served as entertainment in Hoptown. A puff of Indian opium smoke soothed pain resulting from hard work and brought sweet dreams. Running an "opium smoking joint" resulted in fines of $10 and $23 for Ah Sing (1881) and Gee Wah (1886). In 1905, a doctor reported in a death record that Yee Hing, a "Chinaman" from Tombstone, died from opium poisoning at Cochise County Hospital. Until 1906, opium and laudanum were imported and sold openly in the United States and used as medicine by Whites and other nationalities as well. After the 1841 and 1856 Opium Wars, many prominent British and American families profited from the opium trade.

During Chinese new-year celebrations, the Chinese held a huge feast. Ben Traywick's description of forty courses, "consisting partly of Chinese brandy, rat pot pie, bird's nest soup, roasted puppy dogs with caterpillar sauce, shark tails stewed in India ink, monkey hands fried in marrow, kittens fried in batter plus many other delicacies to make a delightful repast," illustrates the elaborate meals that were served at festivals, even in isolated towns like Tombstone.

Tombstone's Chinatown was self-contained but well connected to other Chinese communities throughout the west. Niu Ge, a Taiwan cartoonist/artist who visited Bisbee in 2002, relates how his grandfather toiled in primitive conditions in the copper mines and had to go to a nearby town for acupuncture treatment. Tombstone did have grocers, doctors, gaming rooms and a joss temple, which also served as a meeting hall. People would go to the temple to worship their gods and goddesses, and if they wanted to know their fortune, they could throw a wooden fish and see how it landed.

The Chinese sometimes called each other Ah, followed by their name. Census takers accepted nicknames, which could be the person's first or last name. Women who dealt with Whites would have a nickname like Mary, while the Chinese men in Arizona were usually called John.

Perhaps the most famous Chinese person in Tombstone was China Mary (nee Sing, aka Ah Chum), a plump woman from Zhongshan county. She usually wore brocaded silks and large amounts of Asian jade jewelry. She was influential among Whites and people of other nationalities, and in Hoptown her word was as good as that of a judge or banker. The Whites, who preferred Chinese domestic labor, soon learned that Mary was resourceful in finding workers. She guaranteed the workers' honesty and workmanship. Her warranty was "Them steal, me pay!" All work was done to the employer's satisfaction or it would be redone for free. Payments, however, were made to China Mary - not to the employee.

China Mary managed a well-stocked general store where she dealt in both American and Chinese goods. White men and Asians were both allowed to play in the gambling hall behind her store. They had to abide her rules. China Mary seems to have been an astute investor; she was involved in a number of businesses, including several hand laundries and a restaurant owned by Sam Sing. Mary was also a money lender, and she used her own judgment to determine borrower's credibility. China Mary is also remembered as a generous lady who helped those in need of money or medical care. No sick, injured, or hungry person was ever turned away from her door. She once took a cowboy with a broken leg to Mary Tack's boarding house and paid the medical bill herself. Mary was portrayed by Anna May Wong in a 1960 episode of the Wyatt Earp TV series.

When Mary died of heart failure in 1906, the town folks had a large turnout for her service. A death certificate showed that "Ah Lum" died on December 16, 1906, at the age of 65. Although local official John E. Bacon typed the wrong name (AH-overstrike C(hina) Lum), the date matched the cemetery marker for China Mary, and the certificate was clearly meant for her. China Mary was buried in Boothill Cemetery beside her friend Quong Gu Kee, who died of natural causes on April 23, 1893. Also nearby were Foo Kee, candy store owner, accidentally stabbed in a fight; Hup Lung, for whom no details are available, and two Chinese who died of leprosy. Boothill Cemetery was so named because so many nameless people were buried quickly, with their boots still on.

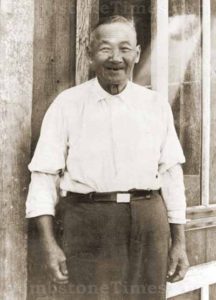

Quong Gu Kee's name is sometimes misspelled Quong Gee Kee, as the result of a county recorder's bad penmanship. Quong was a well-traveled man for those days, having been to Hong Kong, Stockton (CA), Virginia City (NV), Willcox (AZ), and Tombstone. He took over Ah Sing's Can Can restaurant after arriving in Tombstone and proved to possess excellent management skills. An old photo in O. Faulk's Tombstone shows a very spacious modern American restaurant with oil paintings, fine white table cloths, and oak chairs. Only a Buddha statue on the back wall reveals Asian ownership. The Can Can served steaks and ham as well as Chinese food. The cowboys, and gunmen would come for a good time - getting drunk, fighting, and breaking furniture.

Quong's famous customers included Billy Clanton, Wyatt Earp, and Curly Bill. Quong would later recall that Billy Clanton "always eat here and pays, too bad he was gunned down. Earp, nice fella, sometimes he shoots them up and hard on others at times. Curly Brocius eats lots never bad to me."

Quong died in Bisbee, Arizona, and was buried the same day at the Evergreen Cemetery in January 1893. But he was so well liked in Tombstone that when his friends found out, they collected a sizeable fund to exhume and rebury him in Tombstone. An elaborate service, led by an Episcopal minister, was attended by more than 500 people. A Maine state senator delivered the eulogy. A State Tax Commissioner, the founder of Gleeson, Arizona, and Quong's cousins served as pallbearers. Could he have spoken, he would say with his usual smile and swear, "Quong funeral, plitty damn nice".

China Mary's husband, Ah Lum, died from stomach cancer in Arizona. To our knowledge they had no children. He later met Antonia Gomez, a native of Chihuahua at Bar O Ranch restaurant. These two were married and had 4 children: Gilbert (Chinese name unknown) born June 27, 1918, (Bing) Julian-January 7, 1920, Mary(Oni) Ann -February 28, 1922 and William (Hing) - November 18, 1923. Only Bill is still alive. Ah Lum has 9 great-grand children who now live mostly in Arizona and most speak Spanish and English as well.

From the late 19th century to the 1930s, U.S. census records show little evidence of Asians in the area. Maybe a grocer or a gardener in neighboring Pima County and that is about it. It is obvious that all of Cochise County was sparsely populated during this period; each census showed a drop in population in both Tombstone and Bisbee. Records reveal the names of more Chinese who passed away in Cochise county: Gu Kee, son of Quong Gu Kee, born on April 24, 1893, died January 1938; Sing Kee, profession unknown, age 77, died from insanity in Gleeson, March 19, 1928; Ah Lee, died January 23, 1901, from natural causes; Tong Qug, died May 18, 1901; Lee On Loy, age 42, died October 04, 1904; and Wo infant, lived from February 21-25, 1905. Two others, Tong Kee and Sing Kee, were buried in Boothill cemetery.

We do not understand why so many Chinese were interred in Tombstone. The Chinese believed in sending their remains to their birthplace, which in most cases was in China. The bones of China Mary could certainly have been returned to China, because she was affiliated with the Six Companies. However, bad publicity surrounded the express carrier George W. Chapman, which admitted discarding the bones of deceased Chinese, and it is possible that Mary's friends felt it was safer to keep her in Tombstone. At any rate, we believe that the remains were ultimately treated with more respect in a U.S. cemetery. If Mary's bones had been sent to China, they would have been trashed by now, as many Zhongshan tombs have been reclaimed for export factories.

The west has changed a lot since the late 19th century. Former dusty cattle towns with a single dirt road and shacks have morphed into large, bustling cities. The population of Cochise County, where Tombstone is located, increased from 6,938 in 1890 to over 97,600 today. However, Tombstone itself has fewer residents than before, and tourism is its primary industry.

Tombstone, Arizona, is situated southeast of Tucson and has a current population of over 1,500. It has a rich history and is best known for having been a lawless town during the 19th century. The town was made up largely of single men, most of whom were employed by mining companies. The miners worked 60-hour weeks and played hard on their days off. Tombstone was made famous by the gunfight in which Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday shot Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury, and Frank McLaury behind the O.K. Corral. The town became the setting for no fewer than 30 western movies.

The history of Tombstone's Chinese residents, although mostly forgotten, is fascinating as well. Most books written during the period depicted Chinese Americans as drug traffickers and people who loved gambling. One Arizona tourism website cites a historic source that claimed, "The Chinese are highly immoral; they sell children, exercising a system of female slavery." In a 19th-century U.S. census, Chinese females in the west always declared their profession as "prostitutes." On the whole, however, the Chinese were industrious and law abiding. They retained their own heritage and kept very much to themselves.

Around 1870, hundreds of Chinese were employed in the construction of the Southern Pacific railroad through Arizona. Many of these workers were from the Pearl River delta area of Guangdong province. Although the area was an overpopulated poor county at the time, Zhongshan, just north of Macao, is now a modern industrialized city of over a million residents, $4.4 billion in exports annually, and enjoyed a capital income of US $32,000 during year of 2000.

The early Chinese migrant workers came to America through an employment contractor for whom they were to work for a stated term - typically a few years. The business of hiring and managing the employees' affairs was controlled by Chinese Tai Pan and businessmen. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, more commonly known as the Chinese Six Companies (because it represented different regions of Guangdong province), dealt with U.S. immigration matters at the city and state government levels. The Six Companies, which is still in existence, was the most powerful organization acting on behalf of the Chinese outside of China.

Earlier U.S. sources misunderstood the function of Tongs (offices) such as the Six Companies and thought they were involved in gang warfare and selling slaves, as portrayed in Jackie Chan's action-filled movie Shanghai Noon. Tongs actually offered the most advanced employment contracts of the time. The associations paid the workers'passages, found employers, and took care of the employees when they became ill. They were also responsible for sending money home, and they acted as bankers and mail service providers. These services were essential, as the immigrants did not trust the U.S. banking system or Wells Fargo, given the frequent shootouts and robberies. The contractor deducted money for dormitory, food, boat fare, medicine, and also a percentage for its services. The function of Tong acted as a middle man go between for workers and employers. It attempts to guarantee a certain amount of laborers, while proving a safety net for employees.

The workers accepted the premise that they come to America to work hard for a few years so they could pay off their debt to the company. If they earned enough money in Gum Shan (i.e., Golden Mountain), they could return to China and raise a family. In the unfortunate event they died on foreign soil, their remains and soul would be packed and sent home. They were first buried in the Chinese section of a U.S. cemetery. After a year or so, caretakers dug the bodies up, cleaned and soaked the bones in brandy wine (which acted as a preservative), wrapped them in fine silk cloth, and sealed them in an urn. The remains were never wrapped in paper, as was claimed by some early American writers.

When the railroad construction was completed, all the Chinese laborers were let go immediately. The competition of less intensive jobs filled by the whites resulted in the Chinese exclusion Act of 1882. Born survivors, the Chinese managed to settle in nearby towns, finding work in the mines or being redeployed into the service industry. They accepted whatever positions they could get. They worked as woodcutters, miners, cooks, or servants; worked at charcoal manufacturers; or grew vegetables. Most had been farmers in China, and they quickly adapted to the local farming environment. Opportunities arose in work that other men found to be time consuming and undignified, such as doing laundry by hand. Several hundred Chinese settled in Tombstone during the Arizona silver boom of the 1880s.

The Chinese were first regarded with open suspicion by the people of Tombstone, mainly because of their unusual appearance and cultural traits. The men all wore their hair in a queue or pigtail (a subjugation gesture required by the Manchu government, which ruled China from 1644 to 1911). Of the few women who came, some had bound feet. To the puzzlement of other locals, the Chinese drank boiled water infused with "tree leaves" (tea) as a precaution against illness. They ate with wooden sticks while squatting without a chair to sit upon.

White saloon owners, storekeepers, and gamblers bitterly rejected acceptance of the Chinese. The Chinese were included in the Western U.S. census, but in Arizona they were excluded from the state census and not included in the marriage licenses (although they have criminal records). The Whites depended, however, on the work of the Chinese coolies (ku li, meaning hard laborer), who had good work habits and who were willing to do anything for less pay. Despite the harsh wide social gulf that separated them from other people, the Chinese demonstrated a compassion and a recognition of their own value.

Like most cities, Tombstone had its Chinatown. Whites called it "Hoptown." It hopped from Third Street to First Street and from Fremont Street to Toughnut Street. To avoid trouble with residents in other parts of the town, the Chinese hopped in and out of connecting private tunnels. In a town of more than 5000, perhaps 300 to 500 were Chinese who lived in their own quarters.

Pak Gaw, White Dove (i.e., Keno), Mah Jong, and western poker served as entertainment in Hoptown. A puff of Indian opium smoke soothed pain resulting from hard work and brought sweet dreams. Running an "opium smoking joint" resulted in fines of $10 and $23 for Ah Sing (1881) and Gee Wah (1886). In 1905, a doctor reported in a death record that Yee Hing, a "Chinaman" from Tombstone, died from opium poisoning at Cochise County Hospital. Until 1906, opium and laudanum were imported and sold openly in the United States and used as medicine by Whites and other nationalities as well. After the 1841 and 1856 Opium Wars, many prominent British and American families profited from the opium trade.

During Chinese new-year celebrations, the Chinese held a huge feast. Ben Traywick's description of forty courses, "consisting partly of Chinese brandy, rat pot pie, bird's nest soup, roasted puppy dogs with caterpillar sauce, shark tails stewed in India ink, monkey hands fried in marrow, kittens fried in batter plus many other delicacies to make a delightful repast," illustrates the elaborate meals that were served at festivals, even in isolated towns like Tombstone.

Tombstone's Chinatown was self-contained but well connected to other Chinese communities throughout the west. Niu Ge, a Taiwan cartoonist/artist who visited Bisbee in 2002, relates how his grandfather toiled in primitive conditions in the copper mines and had to go to a nearby town for acupuncture treatment. Tombstone did have grocers, doctors, gaming rooms and a joss temple, which also served as a meeting hall. People would go to the temple to worship their gods and goddesses, and if they wanted to know their fortune, they could throw a wooden fish and see how it landed.

The Chinese sometimes called each other Ah, followed by their name. Census takers accepted nicknames, which could be the person's first or last name. Women who dealt with Whites would have a nickname like Mary, while the Chinese men in Arizona were usually called John.

Perhaps the most famous Chinese person in Tombstone was China Mary (nee Sing, aka Ah Chum), a plump woman from Zhongshan county. She usually wore brocaded silks and large amounts of Asian jade jewelry. She was influential among Whites and people of other nationalities, and in Hoptown her word was as good as that of a judge or banker. The Whites, who preferred Chinese domestic labor, soon learned that Mary was resourceful in finding workers. She guaranteed the workers' honesty and workmanship. Her warranty was "Them steal, me pay!" All work was done to the employer's satisfaction or it would be redone for free. Payments, however, were made to China Mary - not to the employee.

China Mary managed a well-stocked general store where she dealt in both American and Chinese goods. White men and Asians were both allowed to play in the gambling hall behind her store. They had to abide her rules. China Mary seems to have been an astute investor; she was involved in a number of businesses, including several hand laundries and a restaurant owned by Sam Sing. Mary was also a money lender, and she used her own judgment to determine borrower's credibility. China Mary is also remembered as a generous lady who helped those in need of money or medical care. No sick, injured, or hungry person was ever turned away from her door. She once took a cowboy with a broken leg to Mary Tack's boarding house and paid the medical bill herself. Mary was portrayed by Anna May Wong in a 1960 episode of the Wyatt Earp TV series.

When Mary died of heart failure in 1906, the town folks had a large turnout for her service. A death certificate showed that "Ah Lum" died on December 16, 1906, at the age of 65. Although local official John E. Bacon typed the wrong name (AH-overstrike C(hina) Lum), the date matched the cemetery marker for China Mary, and the certificate was clearly meant for her. China Mary was buried in Boothill Cemetery beside her friend Quong Gu Kee, who died of natural causes on April 23, 1893. Also nearby were Foo Kee, candy store owner, accidentally stabbed in a fight; Hup Lung, for whom no details are available, and two Chinese who died of leprosy. Boothill Cemetery was so named because so many nameless people were buried quickly, with their boots still on.

Quong Gu Kee's name is sometimes misspelled Quong Gee Kee, as the result of a county recorder's bad penmanship. Quong was a well-traveled man for those days, having been to Hong Kong, Stockton (CA), Virginia City (NV), Willcox (AZ), and Tombstone. He took over Ah Sing's Can Can restaurant after arriving in Tombstone and proved to possess excellent management skills. An old photo in O. Faulk's Tombstone shows a very spacious modern American restaurant with oil paintings, fine white table cloths, and oak chairs. Only a Buddha statue on the back wall reveals Asian ownership. The Can Can served steaks and ham as well as Chinese food. The cowboys, and gunmen would come for a good time - getting drunk, fighting, and breaking furniture.

Quong's famous customers included Billy Clanton, Wyatt Earp, and Curly Bill. Quong would later recall that Billy Clanton "always eat here and pays, too bad he was gunned down. Earp, nice fella, sometimes he shoots them up and hard on others at times. Curly Brocius eats lots never bad to me."

Quong died in Bisbee, Arizona, and was buried the same day at the Evergreen Cemetery in January 1893. But he was so well liked in Tombstone that when his friends found out, they collected a sizeable fund to exhume and rebury him in Tombstone. An elaborate service, led by an Episcopal minister, was attended by more than 500 people. A Maine state senator delivered the eulogy. A State Tax Commissioner, the founder of Gleeson, Arizona, and Quong's cousins served as pallbearers. Could he have spoken, he would say with his usual smile and swear, "Quong funeral, plitty damn nice".

China Mary's husband, Ah Lum, died from stomach cancer in Arizona. To our knowledge they had no children. He later met Antonia Gomez, a native of Chihuahua at Bar O Ranch restaurant. These two were married and had 4 children: Gilbert (Chinese name unknown) born June 27, 1918, (Bing) Julian-January 7, 1920, Mary(Oni) Ann -February 28, 1922 and William (Hing) - November 18, 1923. Only Bill is still alive. Ah Lum has 9 great-grand children who now live mostly in Arizona and most speak Spanish and English as well.

From the late 19th century to the 1930s, U.S. census records show little evidence of Asians in the area. Maybe a grocer or a gardener in neighboring Pima County and that is about it. It is obvious that all of Cochise County was sparsely populated during this period; each census showed a drop in population in both Tombstone and Bisbee. Records reveal the names of more Chinese who passed away in Cochise county: Gu Kee, son of Quong Gu Kee, born on April 24, 1893, died January 1938; Sing Kee, profession unknown, age 77, died from insanity in Gleeson, March 19, 1928; Ah Lee, died January 23, 1901, from natural causes; Tong Qug, died May 18, 1901; Lee On Loy, age 42, died October 04, 1904; and Wo infant, lived from February 21-25, 1905. Two others, Tong Kee and Sing Kee, were buried in Boothill cemetery.

We do not understand why so many Chinese were interred in Tombstone. The Chinese believed in sending their remains to their birthplace, which in most cases was in China. The bones of China Mary could certainly have been returned to China, because she was affiliated with the Six Companies. However, bad publicity surrounded the express carrier George W. Chapman, which admitted discarding the bones of deceased Chinese, and it is possible that Mary's friends felt it was safer to keep her in Tombstone. At any rate, we believe that the remains were ultimately treated with more respect in a U.S. cemetery. If Mary's bones had been sent to China, they would have been trashed by now, as many Zhongshan tombs have been reclaimed for export factories.

The west has changed a lot since the late 19th century. Former dusty cattle towns with a single dirt road and shacks have morphed into large, bustling cities. The population of Cochise County, where Tombstone is located, increased from 6,938 in 1890 to over 97,600 today. However, Tombstone itself has fewer residents than before, and tourism is its primary industry.

References: Traywick, B.T., Wyatt Earp's 13 Dead Men, Red Marie's Publisher, 1998. Burgess, O. R., Quong Kee-Pioneer of Tombstone, 1949 Arizona Highways. Faulk, O., Tombstone, Oxford University Press, 1972. Private communication, Ah Lum's family members, 2006. Private communication, Jodie Hoffman, Tombstone City librarian, 2006.

About the authors: Sam Shueh, a digital librarian, has been researching and writing about California gold country towns for over 20 years. He has written historical articles for magazines and local newspapers and is a member of Morgan Hill (Ca) Historical Society. Eric Chen, of Columbia, Maryland, is a history graduate student with a special fascination for U.S. history.

References: Traywick, B.T., Wyatt Earp's 13 Dead Men, Red Marie's Publisher, 1998. Burgess, O. R., Quong Kee-Pioneer of Tombstone, 1949 Arizona Highways. Faulk, O., Tombstone, Oxford University Press, 1972. Private communication, Ah Lum's family members, 2006. Private communication, Jodie Hoffman, Tombstone City librarian, 2006.

About the authors: Sam Shueh, a digital librarian, has been researching and writing about California gold country towns for over 20 years. He has written historical articles for magazines and local newspapers and is a member of Morgan Hill (Ca) Historical Society. Eric Chen, of Columbia, Maryland, is a history graduate student with a special fascination for U.S. history.